The Comedy of Manners originated in France with Molière's Les Précieuses ridicules (1658), and Molière himself defined it when he said 'correction of social absurdities must at all times be the matter of true comedy'.

The Comedy of Manners originated in France with Molière's Les Précieuses ridicules (1658), and Molière himself defined it when he said 'correction of social absurdities must at all times be the matter of true comedy'.

| NAVIGATION: | Index of Dr. Weller's Class Materials | Index of English 341 Materials |

The Comedy of Manners originated in France with Molière's Les Précieuses ridicules (1658), and Molière himself defined it when he said 'correction of social absurdities must at all times be the matter of true comedy'.

The Comedy of Manners originated in France with Molière's Les Précieuses ridicules (1658), and Molière himself defined it when he said 'correction of social absurdities must at all times be the matter of true comedy'.

Phyllis Hartnoll, The Oxford Companion to the Theatre (London: Oxford UP, 1967), 195.

Comedy of Manners: A term most commonly used to designate the realistic, often satirical, comedy of the Restoration period, as practiced by Congreve and others. It is also used for the revival in modified form, of this comedy a hundred years later by Goldsmith and Sheridan. . . . In the stricter sense of the term, the type is concerned with the manners and conventions of an artificial, highly sophisticated society. . . . The characters are more likely to be types than individualized personalities. Plot, though often involving a clever handling of situation and intrigue, is less important than atmosphere, dialogue, and satire. The dialogue is witty and finished, often brilliant. The appeal is intellectual but not imaginative or idealistic. Satire is directed in the main against the follies and deficiencies of typical characters, such as fops, would-be wits, jealous husbands, coxcombs, and others who fail somehow to conform to the conventional attitudes and manners of the elegant society of the time. This satire is directed against the aberrations of social behavior rather than of human conduct in its larger aspects. A distinguishing characteristic of the comedy of manners is its emphasis upon an illicit love duel, involving at least one pair of witty and often amoral lovers. This prevalence of the immoral "love game" is partly explained by the manners of the time and social groups concerned, and partly by the special satirical purpose of the comedy itself. In its satire, realism, and employment of "humours" the comedy of manners was indebted to Elizabethan and Jacobean comedy. It owed something, of course to the French comedy of manners as practiced by Molière.

C. Hugh Holman, A Handbook to Literature (New York: The Odyssey Press, 1972) 110-111.

Though need make many Poets, and some such

As art and nature have not better'd much;

Yet ours, for want, hath not so loved the stage

As he dare serve th'ill customs of the age:

Or purchase your delight at such a rate

As, for it, he himself must justly hate.

To make a child, now swaddled, to proceed

Man, and then shoot up, in one beard, and weed,

Past threescore years: or, with three rusty swords,

And help of some few foot-and-half-foot words,

Fight over York and Lancaster's long wars:

And in the tiring-house bring wounds to scars.

He rather prays, you will be pleas'd to see

One such, to-day, as other plays should be.

Where neither Chorus wafts you o'er the seas;

Nor creaking throne comes down, the boys to please;

Nor nimble squib is seen, to make afear'd

The gentlewomen; nor roll'd bullet heard

To say, it thunders; nor tempestuous drum

Rumbles, to tell you when the storm doth come;

But deeds, and language, such as men do use:

And persons, such as Comedy would choose

When she would show an image of the times,

And sport with human follies, not with crimes.

Except we make 'm such by loving still

Our popular errors, when we know they're ill.

I mean such errors, as you'll all confess

By laughing at them, they deserve no less:

Which when you heartily do, there's hope left, then,

You, that have so grac'd monsters, may like men.

Ben Jonson, Prologue to Every Man in His Humour -- 1598

A very little history:

A very little history:

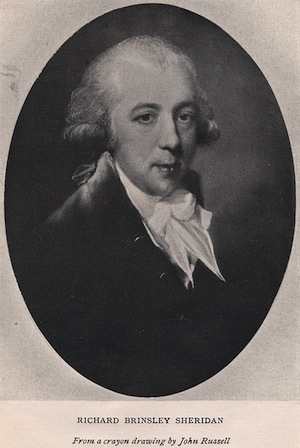

The masterpieces of the genre were the plays of William Wycherley (The Country Wife, 1675) and William Congreve (The Way of the World, 1700). In the late 18th century Oliver Goldsmith (She Stoops to Conquer, 1773) and Richard Brinsley Sheridan (The Rivals, 1775; The School for Scandal, 1777) revived the form. -- Wikipedia: The Comedy of Manners

Friends, a descendent of the Comedy of Manners:

There are two sets of young lovers; in both sets there is one person in whom feelings oversway reason.

Something to listen for and enjoy:

Mrs. MALAPROP: Observe me, Sir Anthony. I would by no means wish a daughter of mine to be a progeny of learning; I don't think so much learning becomes a young woman; for instance, I would never let her meddle with Greek, or Hebrew, or algebra, or simony, or fluxions, or paradoxes, or such inflammatory branches of learning—neither would it be necessary for her to handle any of your mathematical, astronomical, diabolical instruments.—But, Sir Anthony, I would send her, at nine years old, to a boarding-school, in order to learn a little ingenuity and artifice. Then, sir, she should have a supercilious knowledge in accounts;—and as she grew up, I would have her instructed in geometry, that she might know something of the contagious countries;—but above all, Sir Anthony, she should be mistress of orthodoxy, that she might not mis-spell, and mis-pronounce words so shamefully as girls usually do; and likewise that she might reprehend the true meaning of what she is saying. This, Sir Anthony, is what I would have a woman know;—and I don't think there is a superstitious article in it.